An international research team led by the University of Bern has succeeded in developing an electrocatalyst for hydrogen fuel cells that, unlike the catalysts commonly used today, does not require a carbon carrier and is therefore significantly more stable. The new process is industrially applicable and can be used to further optimise fuel cell-powered vehicles without CO2 emissions.

Fuel cells are gaining importance as an alternative to battery-powered electric mobility in heavy-duty transport, especially since hydrogen is a CO2-neutral energy source when obtained from renewable sources. To work efficiently, fuel cells require an electrocatalyst that improves the electrochemical reaction that generates electricity. The catalysts made of platinum-cobalt nanoparticles that are currently used as standard for this purpose have good catalytic properties and require only as little of the rare and expensive platinum as necessary. In order for the catalyst to be used in the fuel cell, it must have a surface with very small platinum-cobalt particles in the nanometre range, which are applied to a conductive carbon carrier material. Since the small particles and the carbon in the fuel cell are exposed to corrosion, the cell loses efficiency and stability over time.

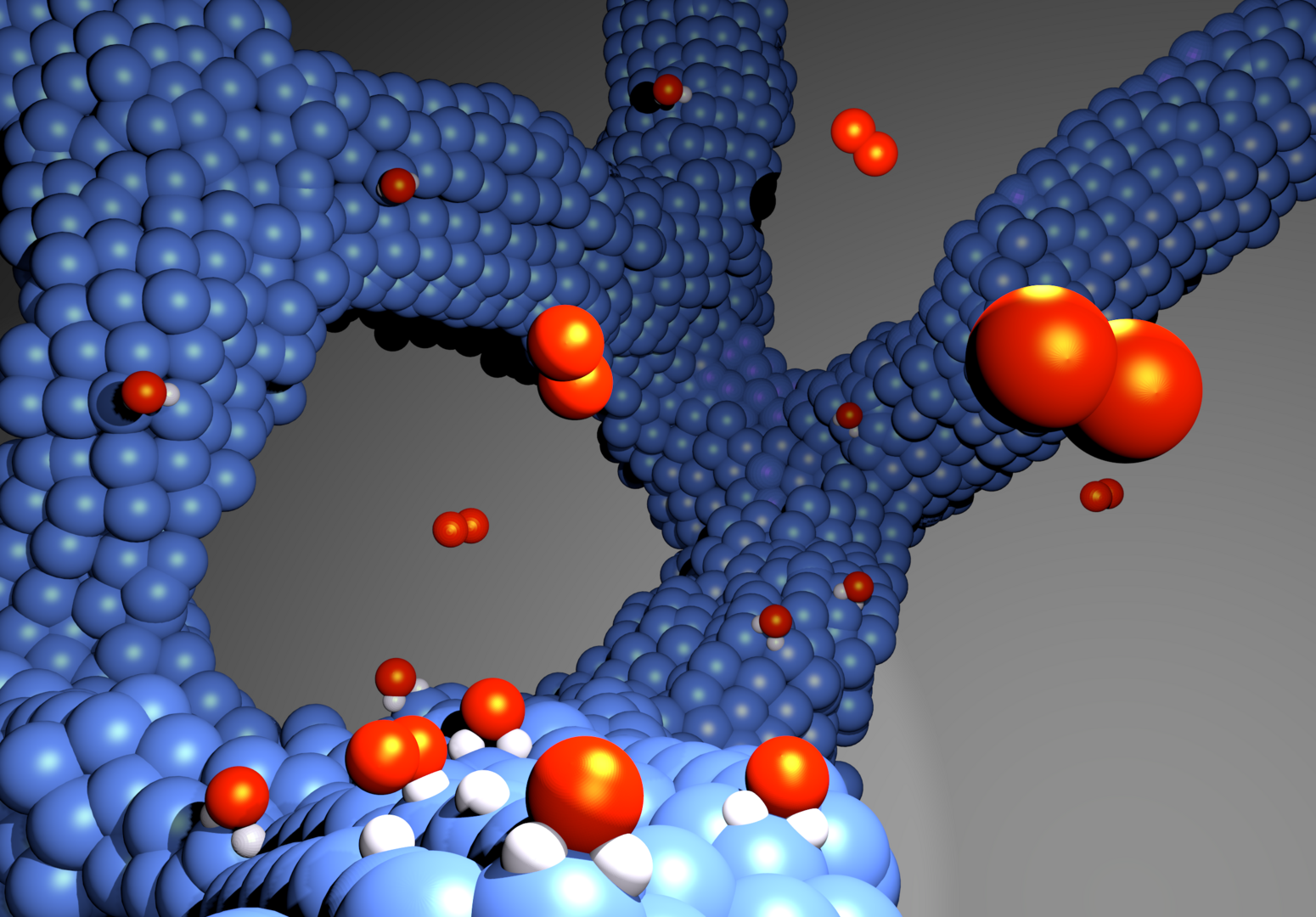

An international team led by Professor Matthias Arenz from the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry (DCB) at the University of Bern has now succeeded in using a special process to produce an electrocatalyst without a carbon carrier. Unlike existing catalysts, it consists of a thin metal network and is therefore more durable. "The catalyst we have developed achieves high performance and promises stable fuel cell operation even at higher temperatures and high current densities," says Matthias Arenz. The results were published in the journal Nature Materials. The study is an international collaboration between the DCB and other institutions, including the University of Copenhagen and the Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology, which also made use of the infrastructure of the Swiss Light Source (SLS) at the Paul Scherrer Institute.

The fuel cell – direct power generation without combustion

In a hydrogen fuel cell, hydrogen atoms are split to generate electricity directly. To do this, hydrogen is fed to an electrode, where it is split into positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons. The electrons flow through the electrode via a high- e and generate electricity outside the cell, which can be used to power a vehicle engine, for example. The protons pass through a membrane that is only permeable to protons and react on the other side with oxygen from the air at a second electrode coated with a catalyst (in this case a platinum-cobalt alloy network), producing water vapour. This is discharged via the "exhaust".

The important role of the electrocatalyst

In order for the fuel cell to produce electricity, both electrodes must be coated with a catalyst. Without a catalyst, the chemical reactions would proceed very slowly. This is particularly true for the second electrode, the oxygen electrode. However, the platinum-cobalt nanoparticles in the catalyst can "melt together" when used in a vehicle. This reduces the surface area of the catalyst and thus the performance of the cell. In addition, the carbon that is usually used to secure the catalyst can corrode when used in road traffic. This impairs the service life of the fuel cell and thus of the vehicle. "Our motivation was therefore to produce an electrocatalyst without a carbon carrier that is still effective," explains Matthias Arenz. Previous, similar catalysts without a carrier material have always had a reduced surface area. Because the size of the surface area is crucial for the activity of the catalyst and thus its performance, these were less suitable for industrial use.

Technology is suitable for industrial use

The researchers were able to put their idea into practice thanks to a special process known as cathode sputtering. In this method, individual atoms of a material (in this case platinum or cobalt) are removed (sputtered) by bombarding them with ions. The removed gaseous atoms then condense to form an adhesive layer. "The special sputtering process and subsequent treatment enable a highly porous structure to be achieved, which gives the catalyst a large surface area and is also self-supporting. This eliminates the need for a carbon carrier," explains Dr Gustav Sievers, lead author of the study from the Leibniz Institute for Plasma Science and Technology.

"This technology is industrially scalable and can therefore also be used for larger production volumes, for example in the automotive industry," says Matthias Arenz. The process can be used to further optimise hydrogen fuel cells for use in road transport. "Our findings are therefore important for the further development of sustainable energy use, especially in view of current developments in the heavy-duty mobility sector," says Arenz.

The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Danish National Research Foundation Centre for High-Entropy Alloy Catalysis, among others.